Discover industry-specific solutions and expertise.

Solve your toughest A&D challenges with Belcan.

Ignite peak performance and efficiency in your business.

Reimagine your manufacturing competitive advantage.

Accelerate growth with customer-focused solutions.

Our data and AI solutions align with your business outcomes and create impactful results.

Personalize learning experiences with education tech and IT solutions—and make learners feel valued.

Create strategies for product, service and process innovation that deliver new growth.

Meet customer demands for a digital, personalized online insurance experience—while reducing risk.

Digitally transform to empower a more intelligent, agile and high-performing enterprise.

Make business decisions based on real-time contextual data with our digital solutions.

Stay ahead of the competition with the latest tech like IoT, machine learning and blockchain.

Deep industry expertise to propel your business into the future.

Explore Belcan’s flexible, custom-tailored solutions.

Solution to turn isolated AI pilots into production-grade agent networks.

Put AI to work and turn opportunity into value.

Accelerate time to value for industrial edge AI.

Maintain high integrity across the AI lifecycle.

Realize the next frontier of enterprise performance.

Enhance operations, boost efficiency, remove technical debt and modernize apps for the future.

Boost operational efficiency, optimize costs and speed product development.

Transform operations through intelligent orchestration, platform integration and strategic partnerships.

Enable a more secure and value-centered business with proven next-gen solutions.

AI insights to inspire enterprise transformation.

Set your modernization up for success with a flywheel strategy.

Develop the technical capabilities needed to create robust agents.

Bridge the gap between strong AI leadership and business readiness.

Explore the latest in AI in our newsletter released bimonthly.

Dive into our forward-thinking research and uncover new tech and industry trends

Explore the top focus areas that are important to Cognizant and our clients.

Explore how our expertise can help you sense opportunities sooner and outpace change.

Discover industry-specific solutions and expertise.

Solve your toughest A&D challenges with Belcan.

Ignite peak performance and efficiency in your business.

Reimagine your manufacturing competitive advantage.

Accelerate growth with customer-focused solutions.

Our data and AI solutions align with your business outcomes and create impactful results.

Personalize learning experiences with education tech and IT solutions—and make learners feel valued.

Create strategies for product, service and process innovation that deliver new growth.

Meet customer demands for a digital, personalized online insurance experience—while reducing risk.

Digitally transform to empower a more intelligent, agile and high-performing enterprise.

Make business decisions based on real-time contextual data with our digital solutions.

Stay ahead of the competition with the latest tech like IoT, machine learning and blockchain.

Deep industry expertise to propel your business into the future.

Explore Belcan’s flexible, custom-tailored solutions.

Solution to turn isolated AI pilots into production-grade agent networks.

Put AI to work and turn opportunity into value.

Accelerate time to value for industrial edge AI.

Maintain high integrity across the AI lifecycle.

Realize the next frontier of enterprise performance.

Solution to turn isolated AI pilots into production-grade agent networks.

Enhance operations, boost efficiency, remove technical debt and modernize apps for the future.

Connect your processes, people and insights across the enterprise with AI-enabled IPA.

Turn big visions into practical realities with expertise that takes you further.

Boost operational efficiency, optimize costs and speed product development.

Transform operations through intelligent orchestration, platform integration and strategic partnerships.

Enable a more secure and value-centered business with proven next-gen solutions.

AI insights to inspire enterprise transformation.

Set your modernization up for success with a flywheel strategy.

Develop the technical capabilities needed to create robust agents.

Bridge the gap between strong AI leadership and business readiness.

Explore the latest in AI in our newsletter released bimonthly.

Keep up with the trends shaping the future of business—and stay ahead in a fast-changing world.

Dive into our forward-thinking research and uncover new tech and industry trends

Explore the top focus areas that are important to Cognizant and our clients.

Explore how our expertise can help you sense opportunities sooner and outpace change.

The Northern European newsletters deliver quarterly industry insights to help your business adapt, evolve, and respond—as if on intuition

Written by Nicolai Tarp

11 January, 2024

Share

5 mins

Too often, in the pursuit of creating new strategies, designs or services for a client, we immediately focus on the future, neglecting the valuable insights derived from existing knowledge.

In this short post, I want to promote the use of desk research as preparation for conducting new research. Understanding the past creates a firm foundation for advancing knowledge within an area; it helps to uncover areas where more research is needed and helps to avoid the pitfall of simply recreating research and insights that have already been “discovered” multiple times in the past.

Digging deep into existing knowledge, past research and current trends will help to narrow the scope of new research. Rather than opening the entire field for inquiry and generating a shallow understanding, you will instead enable yourself to dig deep into areas, topics and elements that play a crucial role in the topic you are researching.

However, it is still important to stay curious and not narrow the research to a point where there is no room for pursuing new interesting areas.

“An effective review creates a firm foundation for advancing knowledge. It facilitates theory development, closes areas where a plethora of research exists, and uncovers areas where research is needed.” (Webster & Watson, 2002).

When diving into the past, it is important to begin by finding and identifying relevant existing research.

As a rule of thumb, the goal of the desk research is to map existing assumptions within the field we are studying, and we want to identify existing literature that helps us do this. We want to understand how the industry is developing (trends), the client and their assumptions (research they have done internally) and if applicable we want to understand how core models of behavior, social and cultural society have been applied to understand the field (often peer-reviewed studies or books).

Peer-reviewed studies can be found through several online channels such as Google Scholar, ensuring critical evaluation of insights from a diverse body of work. Here it is key to have an eye on the number of citations and which journals the papers have been published in. It is important to be critical of the information and rather than relying on the insights from a single paper, try to extract insights from a larger body of work.

Existing research done by the client should be requested early in the project. Often clients do not have a well-structured repository of research, and they don’t always have internal experts who can give an overview. Expect this process of retrieval to take time.

Trend analysis is often the most intangible element of desk research. In this area you can either rely on existing reports from consultancies and the trends they have spotted, or you can use tools driven by big data to create an overview of which trends are developing within the field (like Crunchbase). Just as with peer-reviewed studies, it is important to extract insights from several reports, rather than relying on a single point of view for a comprehensive understanding.

Besides these three types of literature, other types of research might also prove relevant in different project. The objective is, as mentioned, to get a thorough understanding of what has already been researched, and which assumptions exist within the field we want to design for. This will help us find a fruitful direction in our own research and help pinpoint interesting areas of inquiry.

Images by Bas Poppink

Two things are important to keep in mind when beginning to organize the literature and past research; it should be concept-oriented and consider the larger system and structures that influence the subject we are researching.

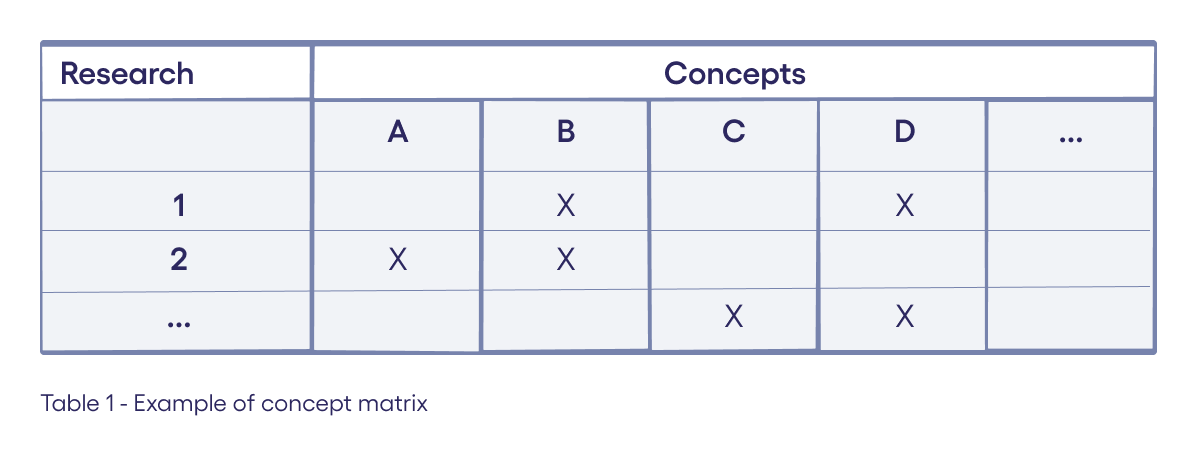

First, rather than organizing based on where the research comes from or who the author is, it is much more valuable for the synthesis to organize based on concepts and focus points in the research. This allows you to spot larger themes that have been covered in-depth, topics that could be interesting to dig deeper into, and themes that have barely been touched upon or not at all.

Second, the people and situations which we are designing for rarely exist independently in this world. They are often part of a much more complex eco-system where human actors are influenced by several different layers of external entities. Considering this larger eco-system that is in place and grouping the insights based on these layers can be a strong way to outline important elements of the eco-system you are designing for.

Images by Bas Poppink

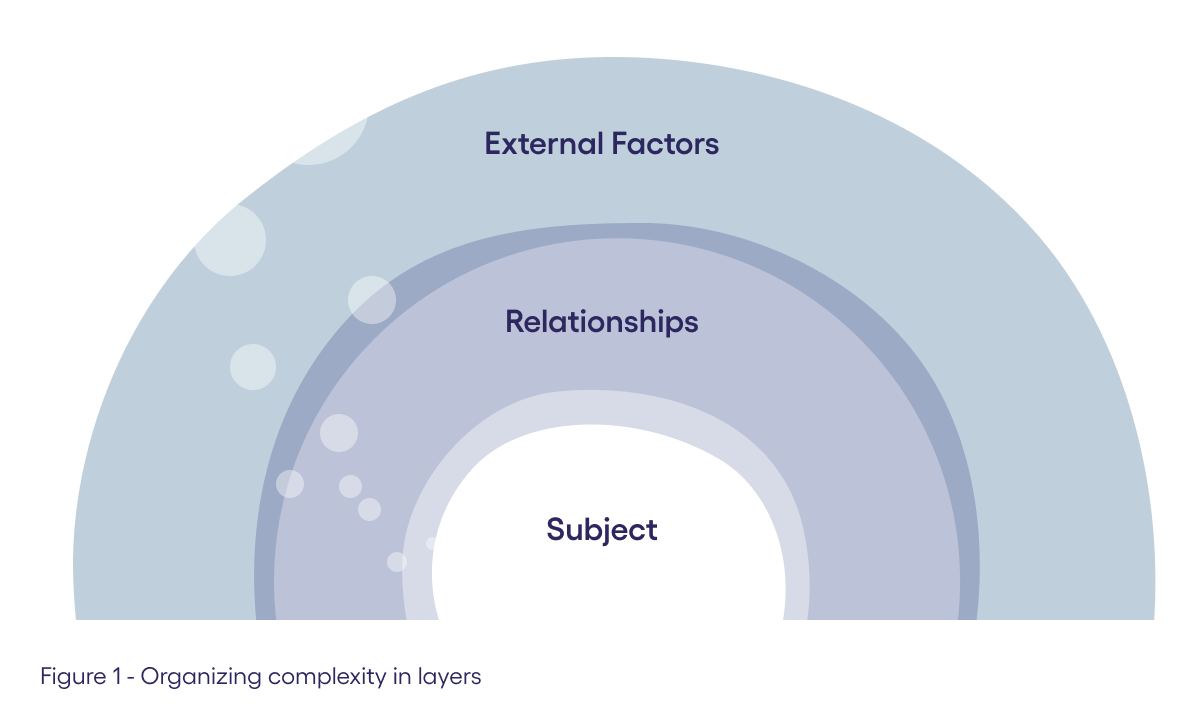

To navigate this complexity, it makes sense to map how different layers within this area have been studied, starting from the center of focus, the subject (see fig. 1).

Take for example the experience of working in agriculture. Here it might make sense to start from the center of the eco-system you want to explore, which could be the farmer and all research describing the farmer’s journey and experience. The next layer could be research describing the relationships around the farmer and their influence on the farmer experience, e.g., retailers, farmer communities, business partners, crops, family, etc. The next layer could be external factors influencing the farmer and the relationships, such as climate, governments, regulations, technology and so on. By considering the layering, or eco-system, you can begin to outline interesting focus areas. The number of layers can be expanded as needed.

A good way of doing both these things is to develop a concept matrix highlighting which concepts that are touched upon in each piece of research.

Images by Bas Poppink

Finally, after reading and organizing the research it is time to synthesize the main observations and findings.

The best way of doing and ultimately presenting this comes down to the project and the desired approach/outcome of a project.

The most straight-forward approach is to present the insights coming out of the concept-matrix by synthesizing the findings from existing research and describing each concept or layer of the eco-system. Like a design process, the quality of the synthesis can be improved through iteration.

Before presenting the findings of the desk research it can be valuable to do two things; stress that these findings are coming out of existing data and present the rigorous process you have gone through, instilling trust in the research process.

When presenting the findings, break it into comprehensible chunks of insides and connections making it easier for the client and audience to understand how each piece of information can be broken down and understood on its own and in a larger context.

A good example of this could be to break the presentation into the layers identified in the ecosystem. Using the example from above a good structure could be 1) Farmer 2) Relationships and 3) External factors. This will allow you to go into each layer individually, while also showing the complexity of the context you are researching.

For each layer you can then go through key concepts and findings arising from the desk research, including which areas have been researched a lot in the past and gaps in past research that would be interesting to understand better. Within each layer it can also make sense to create a structure where you begin with overarching insights or theoretical framings and then slowly break it down into smaller and smaller insights or concepts.

Finally, to ensure that the output of the desk research becomes actionable, it is key to spend some time going through the importance of the findings and how to further use this knowledge. This includes a clear overview of the areas that are well-covered in past research that might act as a foundation for future research as well as highlighting gaps that have not been covered at all, that might prove beneficial to understand better. Remember, the reason for doing this desk research is to help shape future research and make sure that you build on top of existing knowledge when conducting research for a project.

Conclude the desk research presentation by proposing actionable steps, such as a research plan or timeline, illustrating how existing knowledge can shape future research endeavors.

References

Jones, P. H. (2013). Systemic Design Principles for Complex Social Systems. Social Systems and Design, Vol. 1.

Ryan, A. J. (2014). A Framework for Systemic Design. Form Academic, Vol. 7(4).

Webster, J. & Watson, R. T. (2002). Analyzing the Past to Prepare for the Future: Writing a Literature Review. MIS Quarterly, Vol. 26(2).