January 12, 2026

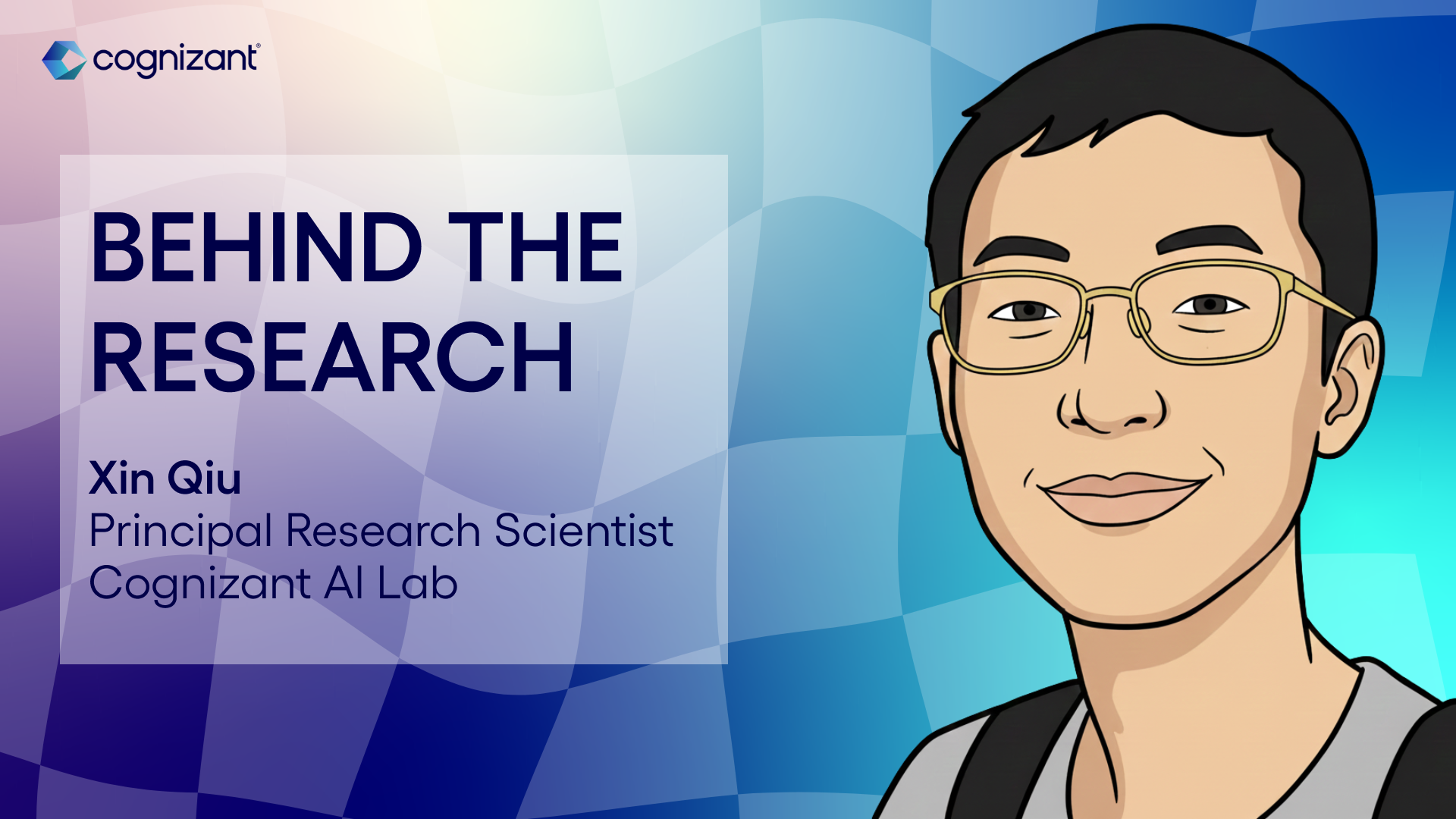

Behind the Research with Xin Qiu

An inside look into the work and expertise from Principal Research Scientist Xin Qiu

Welcome to the second edition of our Behind the Research blog series, featuring Cognizant AI Lab researchers. This series offers an inside look at some of their work and what inspires them, what they’re interested in, and how it shapes the technology that is becoming part of our daily lives. Today, we are interviewing Xin Qiu, Principal Research Scientist at our AI Lab.

Firstly, how did you first get interested in AI and research more generally?

- My interest in AI grew naturally during the early years of my PhD. At the time, I was broadly interested in computer science and drawn to problems that were intellectually challenging, but I didn’t yet have a clear research direction. I took some time exploring different areas until I discovered evolutionary computation, a branch of AI that was not very popular then but deeply intriguing to me.

What attracted me was the creativity involved. Evolutionary computation mimics biological evolution, which opens up many unexplored research questions. As I dug deeper, I began identifying research gaps and challenging open problems, and that process made me increasingly excited about the field.

I started my PhD in 2012, when AI was very different from today. Back then, AI applications were limited to relatively small domains, but over time, the scope expanded dramatically. After graduating, I joined Sentient, where I continued working with the same research team I do now. Being surrounded by passionate and ambitious colleagues further strengthened my commitment to research.

What truly motivates me is the belief that AI can tackle problems that are extremely challenging for humans. Human intelligence itself is a result of natural evolution—we didn’t “design” it. Similarly, AI should learn through interaction with its environment, collecting knowledge and evolving over time. There is no single teacher for intelligence; instead, evolution allows systems to improve continuously. This belief has only grown stronger as AI increasingly transforms the world around us.

What are the main problems you are currently working on, and what makes them meaningful or exciting to you?

- More recently, I’ve been exploring how evolutionary approaches can help move beyond supervised learning. Today’s models mostly learn by mimicking example responses, but we are running out of high-quality data. Nature provides a different blueprint: evolution through mutation, competition, and interaction with the environment.

Evolutionary algorithms allow models to explore new solutions, generate creative behaviors, and learn from interaction rather than imitation. The goal is to build systems that are not explicitly designed by humans but can evolve on their own, proposing new solutions and being evaluated only by how well they perform. In this way, human intelligence is no longer the upper bound—we simply create the environment that enables growth.

What makes this work meaningful to me is the impact. Showing that something widely believed to be impossible can actually work helps expand the boundaries of research and inspires others to think differently.

How do you decide which research questions are worth pursuing and exploring in depth?

- I believe many researchers spend too much time thinking and too little time experimenting. My approach is to try things first. Even if an idea fails, experiments often reveal unexpected phenomena that lead to new insights. Of course, I do literature reviews and look for research gaps, but regardless of how difficult a problem seems, I prefer to try it and let experimental feedback guide me. If the results are good, that’s great. If they’re bad, I become curious about why, and that curiosity often leads to new ideas. The key is to get your hands dirty early and learn directly from experimentation.

Can you share a project you’re especially proud of and what you learned from it?

- Definitely the “Evolution Strategies at Scale: LLM Fine-Tuning Beyond Reinforcement Learning" work. One of my main research focuses is evolving large language models (LLMs) at scale using evolutionary mechanisms. Traditionally, many researchers have believed this was impossible due to the so-called “curse of dimensionality”—the idea that evolutionary methods cannot work effectively when models have billions of parameters.

We decided to challenge that assumption. It was a bold move: evolving models with billions of parameters simultaneously and demonstrating that this approach not only works, but can outperform existing methods such as reinforcement learning. When we succeeded, the results surprised many in the research community and attracted significant attention. I am excited to continue building on this work and its applications.

How do you stay up to date with such a fast-moving field? And are there any areas of AI that you think are underrated or not getting enough attention right now?

- It’s nearly impossible to keep up with everything, as so many new papers are published every day. Social media helps surface important work, but even more valuable is the research community you build—your peers help filter, share, and highlight what truly matters. Sharing work within the community is also the best way to get more eyes on it. That said, I try to stay focused on my own research direction and on papers most relevant to my work, rather than chasing every new trend.

One area I believe is undervalued is how we measure intelligence. Today, we mostly evaluate models based on final performance. But intelligence is not just about outcomes; it’s also about how quickly and efficiently something can learn. For example, if one student scores 90 on an exam but learns incredibly fast, while another scores 95 but learns very slowly, we often assume the second student with the higher score is better. In reality, the faster learner may be more intelligent because they can absorb and adapt to new information more quickly. It’s not just about the final output; it’s also about the learning process. Yet in AI, we rarely measure learning speed or adaptability, and I think this is a critical gap in how we evaluate intelligence.

Looking back, is there anything you would have done differently in your path toward AI research? What advice would you give to someone who is interested in getting into AI research?

- If I could start over, I would invest more effort in open-sourcing my code and improving code quality. Making research more accessible allows others to build on it and amplifies its impact.

I would also explore a wider range of directions early on, rather than narrowing too quickly. I think there is an opportunity in being open before becoming specialized to really explore your interests and find your niche. But in that process, for those entering AI research, my advice is not to chase other people’s work. Following trends can lead to quick, incremental results, but truly impactful research requires ambition.

Work on problems you believe are important, especially problems that others think are unsolvable. Chase that challenge and avoid focusing only on short-term gains with only follow up work and low hanging fruit that answer the easy questions. Genuine curiosity is the most important driver of great research. In many ways, being a good researcher means staying childlike in your curiosity.

Your AI agent has a dashboard of “human stats” about you. What three silly metrics is it tracking?

How many bad beats I suffer in poker games

How many times my daughter calls me “Baba”

Accurate lap time of our robot dog CAILEY in our lab races

Xin is a research scientist that specializes in uncertainty quantification, evolutionary neural architecture search, and metacognition, with a PhD from National University of Singapore