January 13, 2026

Neuro SAN and MCP: Agent Interconnectivity with Agent Registries

In this post, we break down what makes a high-quality agent registry and how Neuro SAN and MCP support scalable agent-to-agent integration..

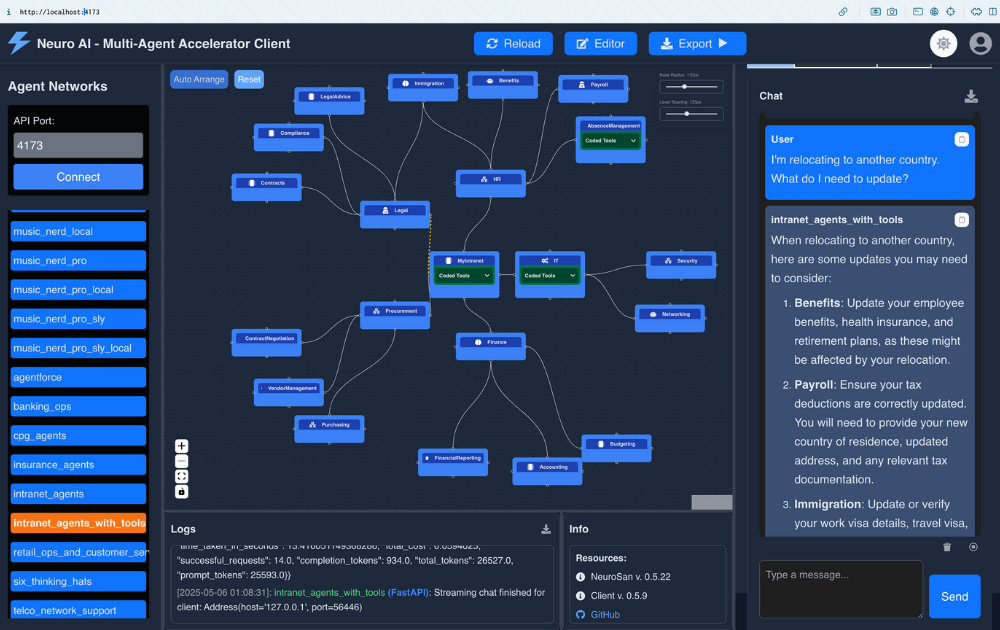

The concept of agent registries is quickly emerging as a foundational building block for agentic systems. As more platforms adopt agent-based architectures, the need for a shared, discoverable way to describe and invoke agent capabilities becomes more urgent. Both Neuro SAN and MCP agent registries answer that need by acting as an integration catalog focused not on static APIs, but on agent capabilities described in natural language that can be consumed by both humans and other agents. In doing so, they bridge the gap between traditional API registries and service catalogs, shifting the emphasis from endpoints to agent skills.

At their core, MCP registries provide a scoped, platform-neutral exchange layer. They allow a wide range of calling agent types to query what other agents or tools can do, without tightly coupling those callers to specific agent framework implementations. This neutrality is what makes MCP a credible attempt at a lingua franca for agentic systems, though in its current form it does have some weak points (discussed below).

Neuro SAN agent servers share this registry-as-exchange aspect of their functionality with MCP registries. In fact, with Neuro SAN, every server can by default act as its own MCP registry for the agent networks it hosts. MCP visibility can be configured on a network-by-network basis without writing code, allowing teams to precisely control what capabilities are exposed. This configuration-driven approach supports scalability while respecting security boundaries.

What Makes a Quality Agent Registry

A high-quality agent registry does not start from scratch. It builds on the lessons learned from API registries and inherits their expectations around authentication, authorization, security, governance, and operational consistency. These concerns are not optional; without them, registries risk becoming brittle or unsafe integration points.

At the same time, there are clear limits to what a registry itself should enforce. Security guardrails and privilege boundaries are ultimately the responsibility of the underlying agents and tools, not the registry-as-exchange. Attempting to enforce these concerns at the registry level can easily become either too heavy—by introducing intermediary agents and complexity—or too weak, by relying on declarative tags that can be faked or quickly become outdated as agent implementation changes. While additional layers can be introduced to support security controls automatically, they come at a cost of deployment complexity and latency.

One of the most important realities to internalize is that any client is itself very likely to be an agent, not a human. That agent may pass everything it receives directly into an uncontrolled chat stream or LLM system with its own standards for what is safe to log, which are very likely not aligned with your own. For this reason, registries and the agents behind them must be designed with the assumption that anything returned could be widely shared. Platforms like Neuro SAN address this by ensuring that private data remains private via the sly_data mechanism and never leaks into other agents' chat streams. MCP registries, though, have no such layer of enforcement for private data; the MCP ecosystem still relies on informal guidance—effectively “don’t do that”—and this lack of strong separation will limit the growth of inter-organizational MCP-oriented agent networks until it is addressed at a more fundamental level.

Public vs. Private Agent Registries

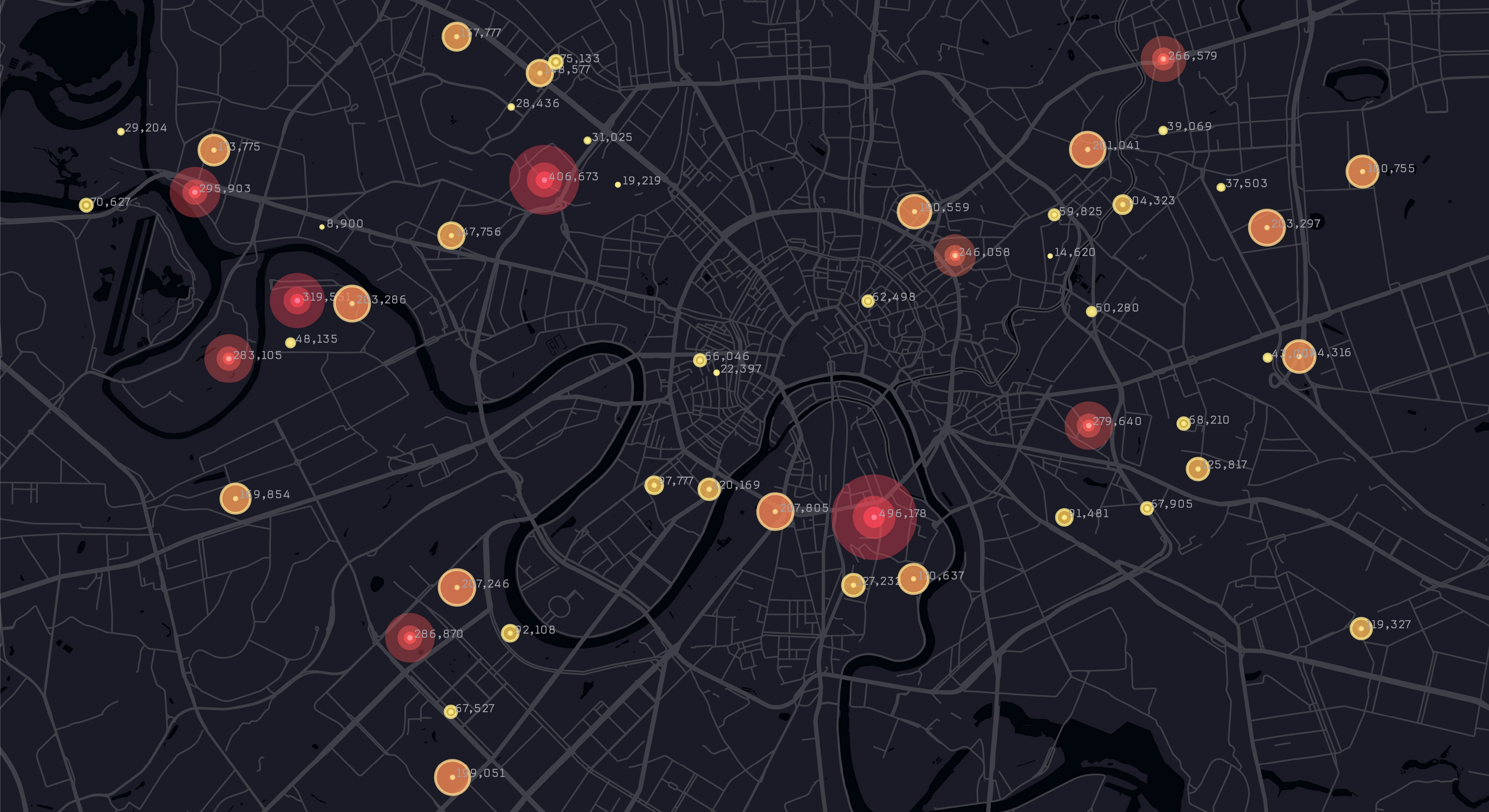

I like to think of individual agent registries as each residing at a cross section of a reasonable grouping of information provided by the agents it hosts and a reasonable security perimeter. So, an enterprise likely should not have a single internal agent registry, but rather multiple registries for these internal security concerns, so the information and access concerns can be properly scoped.

The decision to use a public or private agent registry closely mirrors the same decision for API registries and should be driven by use case and security requirements. Most enterprise-internal use cases today are better served by private agent registries. The risk of exposing corporate secrets or sensitive information through a public registry is still quite high without proper care taken to insulate private data (though Neuro SAN has the ability to help quite a bit in mitigating that).

Public agent registries, however, are entirely appropriate for open or widely knowable domains. Public datasets and services—such as Wikipedia content, public GitHub repositories, or airline flight information—are natural candidates. In these cases, the information is already accessible, and exposing it as agent-consumable capabilities simply reduces friction.

The best way to think about how to expose agents is on a strict need-to-know basis. If agents are intended only for internal use, there is no benefit in exposing them publicly. Conversely, organizations may choose to expose a carefully curated set of public-facing capabilities while keeping sensitive agents private, perhaps as an implementation detail of those public-facing agents. A company could, for example, offer public agents for booking or searching while keeping pricing logic or user data management strictly internal.

Agent Abstraction

Abstraction is one of the most nuanced design decisions in an agent registry. Registries tend to sit at the intersection of a logical grouping of capabilities and a security perimeter. For enterprises, this often argues against a single, monolithic internal registry. Multiple agent registries, each aligned to a specific security boundary or information domain, allow access and data exposure to be properly scoped.

From a design perspective, lower-level, granular tools tend to be more flexible. Mapping each tool to a single, atomic capability avoids premature abstraction and overuse of an overly complicated agent to get at simpler tasks performed within. Higher-level abstractions are better built at a composite level, where agents combine multiple tools into richer skills, and agent networks then collaborate to produce even more advanced behaviors. Neuro SAN’s configuration-based agent network approach is ideal for providing this kind of scalability at all these levels of complexity just described.

For external consumers, however, convenience matters. A single public-facing agent registry can make sense, provided it only exposes agents that are guaranteed not to leak internal or private data.

Practical Guidance for Builders

When building an agent registry, start by understanding what data must remain private and what credentials are required for it to move safely. Treat any client of an MCP registry (in particular) as if it is going to send its answers in the chat stream all over the world. This all said, you don’t have to be afraid; you just have to be mindful of what goes out.

Leverage existing API platforms and their mature security and governance capabilities like Apigee, Mulesoft, Boomi, etc., rather than reinventing them. Start small with a limited set of agents, each providing a single, well-defined capability. Test these tools with low-scope agents before expanding. Group agents by similar capabilities, and let agent collaboration emerge naturally rather than forcing them into the agents’ instructions.

Taken together, these practices position agent registries as the next evolution of integration catalogs—purpose-built for agentic networks and webs, powerful when used thoughtfully, and risky when their boundaries are misunderstood.

Daniel Fink is an AI engineering expert with 15+ years in AI and 30+ years in software — spanning CGI, audio, consumer devices, and AI.